Do you know what all the markings on your tires mean?

If you're in the market for new tires, all of the variables in tire specifications and the confusing jargon you might hear from tire salesmen or "experts" might make your purchase rather stressful. Or maybe you just want to fully understand the tires you already have, the concepts at work, the significance of all of those sidewall markings. What does all this stuff mean in regular terms?

In this article, we will explore how tires are built and see what's in a tire. We'll find out what all the numbers and markings on the sidewall of a tire mean, and we'll decipher some of that tire jargon. By the end of this article, you'll understand how a tire supports your car, and you'll know why heat can build up in your tires, especially if the pressure is low. You'll also be able to adjust your tire pressure correctly and diagnose some common tire problems!

Contents

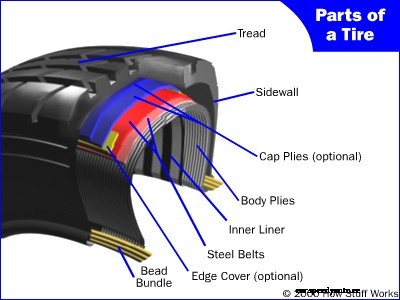

As illustrated below, a tire is made up of several different components.

All of these components are assembled in the tire-building machine. This machine ensures that all of the components are in the correct location and then forms the tire into a shape and size fairly close to its finished dimensions.

At this point the tire has all of its pieces, but it's not held together very tightly, and it doesn't have any markings or tread patterns. This is called a green tire. The next step is to run the tire into a curing machine, which functions something like a waffle iron, molding in all of the markings and traction patterns. The heat also bonds all of the tire's components together. This is called vulcanizing. After a few finishing and inspection procedures, the tire is finished.

Each section of small print on a tire's sidewall means something:

Tire Type

The P designates that the tire is a passenger vehicle tire. Some other designations are LT for light truck, and T for temporary, or spare tires.

Tire Width

The 235 is the width of the tire in millimeters (mm), measured from sidewall to sidewall. Since this measure is affected by the width of the rim, the measurement is for the tire when it is on its intended rim size.

Aspect Ratio

This number tells you the height of the tire, from the bead to the top of the tread. This is described as a percentage of the tire width. In our example, the aspect ratio is 75, so the tire's height is 75 percent of its width, or 176.25 mm ( .75 x 235 = 176.25 mm, or 6.94 in). The smaller the aspect ratio, the wider the tire in relation to its height.

High performance tires usually have a lower aspect ratio than other tires. This is because tires with a lower aspect ratio provide better lateral stability. When a car goes around a turn lateral forces are generated and the tire must resist these forces. Tires with a lower profile have shorter, stiffer sidewalls so they resist cornering forces better.

Tire Construction

The R designates that the tire was made using radial construction. This is the most common type of tire construction. Older tires were made using diagonal bias (D) or bias belted (B) construction. A separate note indicates how many plies make up the sidewall of the tire and the tread.

Rim Diameter

This number specifies, in inches, the wheel rim diameter the tire is designed for.

Uniform Tire Quality Grading

Passenger car tires also have a grade on them as part of the uniform tire quality grading (UTQG) system. You can check the UTQG rating for your tires on this page maintained by the U.S. National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA). Your tire's UTQG

rating tells you three things:

Service Description

The service description consists of two things:

Calculating the Tire Diameter

Now that we know what these numbers mean, we can calculate the overall diameter of a tire. We multiply the tire width by the aspect ratio to get the height of the tire.

Then we add twice the tire height to the rim diameter.

This is the unloaded diameter; as soon as any weight is put on the tire, the diameter will decrease.

There are a lot of different terms used today in the tire industry. Some of them actually mean something and some do not. In this section, we'll try to explain what some of the terms mean.

All-Season Tires with Mud and Snow Designation

If a tire has MS, M+S, M/S or M&S on it, then it meets the Rubber Manufacturers Association (RMA) guidelines for a mud and snow tire. For a tire to receive the Mud and Snow designation, it must meet these geometric requirements (taken from the bulletin "RMA Snow Tire Definitions for Passenger and Light Truck (LT) Tires"):

1. New tire treads shall have multiple pockets or slots in at least one tread edge that meet the following dimensional requirements based on mold dimensions:

2. The new tire tread contact surface void area will be a minimum of 25 percent based on mold dimensions.

The rough translation of this specification is that the tire must have a row of fairly big grooves that start at the edge of the tread and extend toward the center of the tire. Also, at least 25 percent of the surface area must be grooves.

The idea is to give the tread pattern enough void space so that it can bite through the snow and get traction. However, as you can see from the specification, there is no testing involved.

To address this shortcoming, the Rubber Manufacturers Association and the tire industry have agreed on a standard that does involve testing. The designation is called Severe Snow Use and has a specific icon (see image at right), which goes next to the M/S designation.

In order to meet this standard, tires must be tested using an American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM) testing procedure described in "RMA Definition for Passenger and Light Truck Tires for use in Severe Snow Conditions":

Tires designed for use in severe snow conditions are recognized by manufacturers to attain a traction index equal to or greater than 110 compared to the ASTM E-1136 Standard Reference Test Tire when using the ASTM F-1805 snow traction test with equivalent percentage loads.

These tires, in addition to meeting the geometrical requirements for an M/S designation, are tested on snow using a standardized test procedure.They have to do better than the standard reference tire in order to meet the requirements for Severe Snow Use.

Hydroplaning

Hydroplaning can occur when the car drives through puddles of standing water. If the water cannot squirt out from under the tire quickly enough, the tire will lift off the ground and be supported by only the water. Because the affected tire will have almost no traction, cars can easily go out of control when hydroplaning.

Some tires are designed to help reduce the possibility of hydroplaning. These tires have deep grooves running in the same direction as the tread, giving the water an extra channel to escape from under the tire.

You may have wondered how a car tire with 30 pounds per square inch (psi) of pressure can support a car. This is an interesting question, and it is related to several other issues, such as how much force it takes to push a tire down the road and why tires get hot when you drive (and how this can lead to problems).

The next time you get in your car, take a close look at the tires. You will notice that they are not really round. There is a flat spot on the bottom where the tire meets the road. This flat spot is called the contact patch, as illustrated here.

If you were looking up at a car through a glass road, you could measure the size of the contact patch. You could also make a pretty good estimate of the weight of your car, if you measured the area of the contact patches of each tire, added them together and then multiplied the sum by the tire pressure.

Since there is a certain amount of pressure per square inch in the tire, say 30 psi, then you need quite a few square inches of contact patch to carry the weight of the car. If you add more weight or decrease the pressure, then you need even more square inches of contact patch, so the flat spot gets bigger.

You can see that the underinflated/overloaded tire is less round than the properly inflated, properly loaded tire. When the tire is spinning, the contact patch must move around the tire to stay in contact with the road. At the spot where the tire meets the road, the rubber is bent out. It takes force to bend that tire, and the more it has to bend, the more force it takes. The tire is not perfectly elastic, so when it returns to its original shape, it does not return all of the force that it took to bend it. Some of that force is converted to heat in the tire by the friction and work of bending all of the rubber and steel in the tire. Since an underinflated or overloaded tire needs to bend more, it takes more force to push it down the road, so it generates more heat.

Tire manufacturers sometimes publish a coefficient of rolling friction (CRF) for their tires. You can use this number to calculate how much force it takes to push a tire down the road. The CRF has nothing to do with how much traction the tire has; it is used to calculate the amount of drag or rolling resistance caused by the tires. The CRF is just like any other coefficient of friction: The force required to overcome the friction is equal to the CRF multiplied by the weight on the tire. This table lists typical CRFs for several different types of wheels.

Tire TypeCoefficient of Rolling FrictionLow rolling resistance car tire0.006 - 0.01Ordinary car tire0.015Truck tire0.006 - 0.01Train wheel0.001

Let's figure out how much force a typical car might use to push its tires down the road. Let's say our car weighs 4,000 pounds (1814.369 kg), and the tires have a CRF of 0.015. The force is equal to 4,000 x 0.015, which equals 60 pounds (27.215 kg). Now let's figure out how much power that is. If you've read the HowStuffWorks article How Force, Torque, Power and Energy Work, you know that power is equal to force times speed. So the amount of power used by the tires depends on how fast the car is going. At 75 mph (120.7 kph), the tires are using 12 horsepower, and at 55 mph (88.513 kph) they use 8.8 horsepower. All of that power is turning into heat. Most of it goes into the tires, but some of it goes into the road (the road actually bends a little when the car drives over it).

From these calculations you can see that the three things that affect how much force it takes to push the tire down the road (and therefore how much heat builds up in the tires) are the weight on the tires, the speed you drive and the CRF (which increases if pressure is decreased).

If you drive on softer surfaces, such as sand, more of the heat goes into the ground, and less goes into the tires, but the CRF goes way up.

Underinflation can cause tires to wear more on the outside than the inside. It also causes reduced fuel efficiency and increased heat buildup in the tires. It is important to check the tire pressure with a gauge at least once a month.

Overinflation causes tires to wear more in the center of the tread. The tire pressure should never exceed the maximum that is listed on the side of the tire. Car manufacturers often suggest a lower pressure than the maximum because the tires will give a softer ride. But running the tires at a higher pressure will improve mileage.

Misalignment of the wheels causes either the inside or the outside to wear unevenly, or to have a rough, slightly torn appearance.

For more information on tires and related topics, check out the links on the next page.

Originally Published: Sep 19, 2000

Related Articles

More Great Links