Of all systems on your vehicle, the brake system could be the most important. When the driver steps on the brake pedal, a brake booster amplifies the force, pushing directly into the master cylinder. The master cylinder converts linear motion and force into hydraulic pressure. The “master” cylinder distributes this pressure to the brake calipers or wheel cylinders, also known as “slave” cylinders. At the slave cylinders, hydraulic pressure is converted back to linear motion and force, to compress brake pads or expand brake shoes. In turn, the friction generated can keep a vehicle from moving, or slow it down, converting its kinetic energy into heat energy.

Here, we discuss how the master cylinder works and what symptoms are associated with master cylinder failure. Some of this information may not apply to some newer brake systems, which feature integrated electrohydraulic boosting, but the theory is similar.

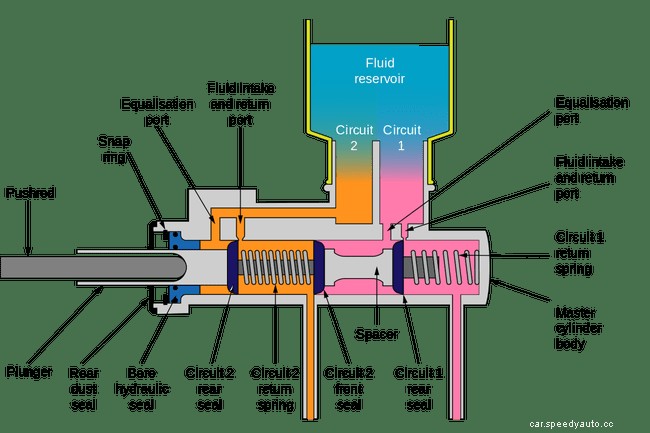

Before learning how the master cylinder might fail and how to recognize problems, it’s good to understand how it works. On top of the master cylinder is the brake fluid reservoir, usually attached directly, but sometimes connected by a hose. Gravity feeds brake fluid to the master cylinder, filling the space around two pistons, one for each circuit. At rest, return springs push the pistons to the back of the master cylinder, releasing all pressure from the brake lines.

When the driver depresses the brake pedal, the brake pedal pushrod pushes on the primary piston. As the primary piston moves forward, it moves past the intake port and generates hydraulic pressure, which is directed to the primary brake circuit and the secondary piston. Because brake fluid doesn’t compress, the secondary piston moves forward at the same time, generating hydraulic pressure in the secondary brake circuit. Depending on brake system design, primary and secondary circuits may vary, usually front (primary) and rear (secondary), but some vehicles split the hydraulic system diagonally or some other way.

Like all mechanical and hydraulic devices, the master cylinder will eventually wear out. Depending on use, the typical master cylinder might last 60,000 to 200,000 miles. Highway commuters use the brakes less often than city taxis, for example, so their master cylinders tend to last longer. The mechanical parts of the master cylinder, the springs, and pistons are so simple that failure is almost unheard of. On the other hand, the rubber seals can wear out and degrade over time, leading to internal or external leaks. Here are a few symptoms of master cylinder failure, along with some basic brake diagnostic tips.

For the most part, problems with the master cylinder are solved by replacing the master cylinder entirely. True, they can be rebuilt, but such a critical component is best left to the professionals. Some new or rebuilt master cylinders may not come with the reservoir, so the old one will need to be cleaned and installed on the new one. Master cylinder bench-bleeding and installation tends to be messy, so be sure to cover painted surfaces and clean up everything as soon as you can get all the lines attached and before the reservoir runs out.