You’ve heard the term turbocharged engine so many times that you’ve formed a basic idea of how it works, but you never got an answer to the question of how much horsepower does it add?

The answer is more complex than it seems, as adding a turbocharger to an engine generally involves a number of other upgrades. In general, a single turbocharger is responsible for a power increase of 10 to 50%.

My favorite definition of a turbocharger has been coined by none other than Jeremy Clarkson:

A turbo: exhaust gasses go into the turbocharger and spin it. Witchcraft happens and you go faster.

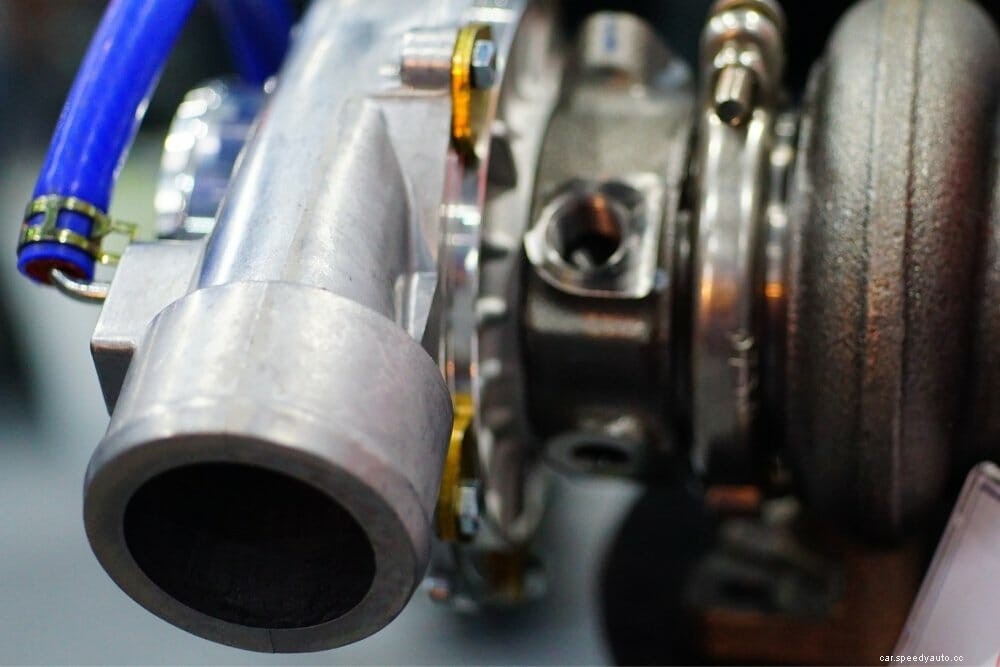

What makes the quote funnier is that it’s not far from the truth – the turbocharger is a turbine propelled by exhaust gases and sucks in air to result in increased airflow through the intake. More air means more oxygen inside the air-fuel mixture, better fuel burn, and more power generated through each cycle.

Apart from the turbine itself, the system has an intercooler that reduces the gas temperatures, a wastegate valve that limits the boost pressure level, and a blow-off valve that expels unused pressure from the system.

Jason from Engineering Explained has a great video on turbochargers that explains the basic principles in just a few minutes.

I’ve said in the introduction that in most cases, a turbocharger adds 10 to 50% more power. This is a generalization, and the actual power increase can easily pass 100%. For that to happen, the fuel injection system needs to be upgraded at the very least.

My favorite example of turbocharger benefits is Volkswagen’s 1.9-liter R4 TDI turbocharged diesel engine. They’ve made almost a dozen variants of this engine, with power ranging from 74 horsepower, all the way to 158 horsepower.

Twin-turbo and bi-turbo are also very common. Twin-turbo refers to two identical turbines that split the load on engines with 6 or more cylinders. Bi-turbo (or sequential turbo) refers to a system with a small and a large turbocharger. The smaller turbo handles low-RPM to mitigate turbo-lag, while the second, or both engage at higher RPM to drastically increase power.

Then you have engine blocks with 6 or 8 cylinders that utilize a quad-turbo setup. It uses two bi-turbo setups to create a massive amount of power – a naturally aspirated engine capable of taking a quad-turbo setup can easily double the horsepower.

Turbo boost is a positive pressure created by the turbocharger. In other words, it represents the pressure difference between the intake manifold and atmospheric pressure. It’s measured in psi or bar, with higher values resulting in greater power.

However, over-boosting would exceed the limits of what the turbocharger and the engine can take, and cause a variety of problems: engine knocking, overheating, pre-ignition, and component failure.

The main operating principle of a turbocharger involves using exhaust gases as a catalyst to push more air into the intake. However, this leads to the main flaw of the turbochargers – turbo lag.

When the engine is running at low RPM, the volume of exhaust gases isn’t high enough to create a sufficient boost. The vehicle will feel like it has half of its power at its disposal, which in some ways it does, as it runs like a naturally aspirated engine. It’s only when you raise the RPM to a sufficient level that the boost kicks in and provides a surge in power.

With a single-turbine engine, turbocharged power is always offset by turbo lag. The bigger the turbine gets, the more pressure is required until it can start boosting, hence the longer turbo lag. On the other hand, small turbines will engage just above idle RPM, but cannot deliver enough boost for a lot of power.

Turbo lag occurs when you keep your foot off the gas, which is normal when braking and shifting gears. However, there are a couple of ways around it.

The first way to mitigate turbo large is to use the heel-toe method. Brake first, then apply the clutch. With the transmission disengaged, you can use the heel of your right foot to step on the gas as you’re downshifting. Move your foot on the gas as you’re releasing the clutch, and turbo boost will kick in sooner.

Heel-toe isn’t doable in all vehicles and can be rather awkward depending on your seating position. There is a simplified process that provides the same results, it just takes a bit longer to do. First, you break until you’ve decelerated sufficiently. Engage the clutch, and as you’re shifting gears, use your right foot to step on the gas once or twice.

Obviously, both methods require a manual gearbox to use. They’re primarily designed to help you handle an overtake where you’re decelerating towards a vehicle, but you see an opportunity to overtake it come up. Instead of losing time on turbo lag, the car will be ready to deliver full power as soon as the left lane has cleared.

I use both methods frequently when driving uphill. When there’s a sharp corner, I need to break, but I don’t want to lose the power necessary to keep going. By mitigating turbo lag, I can still have the power to tackle the corner without issues and increase my speed if it’s safe to do so.

Turbochargers bring a lot of benefits. First, they allow you to drive a vehicle with a smaller engine displacement and still have comparable power to larger, naturally aspirated engines, while consuming significantly less fuel.

The only real drawback of the turbochargers is the added complexity of the engine. The more parts you add, the more parts are at risk of breaking. You shouldn’t worry about this with a single-turbocharger setup, but if a car has two or four turbines, take into consideration how expensive it’ll be to repair or replace them.

Next to the superchargers, turbochargers are the best way of increasing the power of an engine without increasing its displacement or creating high tolerances that would severely affect the cost of manufacture.

On average 2,000 RPM is enough to generate enough exhaust pressure to spin the turbine and create a turbo boost. The exact RPM depends on the size of the turbine – smaller turbines will engage sooner, while larger turbines are often designed in a bi-turbo layout, with a smaller turbine creating power at low RPM.

Factory-mounted turbochargers are not bad for your engine. The manufacturer has designed the engine so it can withstand the turbo boost without being damaged. However, modifying a stock turbocharger or installing a custom turbocharger can push the engine past its tolerance levels and cause damage.

In does. Six or eight-cylinder engines have split exhaust manifolds, and each creates enough exhaust gases to power one turbocharger, which then creates enough boost to supply all the cylinders. In terms of percentage, the power increase may be the same as for single-turbo engines, but in terms of numbers, twin-turbo delivers a lot more power.

Turbochargers have become a necessity for engines with smaller displacements, significantly increasing their power and making them more useful on open roads. Larger, inline-6, V6, and V8 engines don’t necessarily need a turbocharger, but they can be added in pairs for a massive power boost.

If you’re browsing car offers and wondering if you need a turbocharged engine, I would highly recommend it for any 4-cylinder engine. For SUVs and trucks, a turbocharger is very useful for all but the largest V8 options.

You may check these other articles for more information:

How To Use Octane Booster: Complete Guide

How To Get 30+ Mpg With A Duramax

How Much Horsepower Does a Camshaft Add?